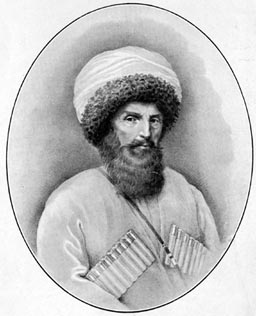

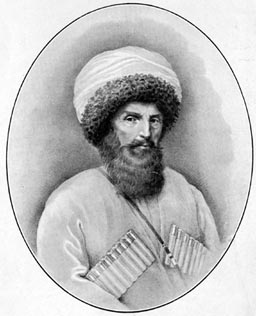

Imam Shamil (1797-1871)

Imam Shamil

Introduction

Imam Shamil was the political, military, and religious leader of the Caucasian Muslims in their 19th century struggle for national liberation. Shamil, himself a Dagestani, founded Muradism, a movement that united Dagestan and Chechnya in their struggle for freedom against Russian domination. He also advocated the abandonment of the tribal system that had resulted in endless feuds among the Caucasian clans, and attempted to restore Sharia, or Muslim law. The peoples of both Dagestan and Chechnya revered him as their Imam—their divinely inspired religious leader.

Shamil exercised a combination of religious, administrative, and military powers. Prince Ilya Orbeliani (brother of Grigol Orbeliani, a prominent Georgian poet and military commander), who spent eight months as Shamil’s hostage, wrote in his book Eight Months in Shamil’s Captivity:

[Shamil] stands out for his shrewdness, determination, valor, and personal merits. Shamil’s predecessors, Ghazi Mohammed, Mollah and Hamzat Beg, were killed in 1832 and 1834. The former died during an assault on the Russians. Hamzat Beg was killed in Dagestan by a Naib (local leader). Shamil soon became increasingly popular among the Dagestanis.

His reputation was not marred even by several military defeats to the Russian army in 1835-1836, and his subsequent, highly successful military campaigns of 1837 brought him further renown. His influence spread to Chechnya and the other Caucasian Muslim countries, where he was referred to as the "Eagle of the Mountains."

Shamil’s antipathy towards the occupying Russians extended to their fellow Christians within the Russian Empire, the Georgians, whose nation borders on Dagestan to the west. His ultimate goal was the conquest of the entire Caucasus region and the establishment of an Islamic Nation with the Georgian capital of Tbilisi as its center. In his pursuit of this divine mission, Shamil enjoyed the support of Turkey, whose Sultan sent troops to aid him.

Shamil’s troops frequently launched raids on Georgia, with the province of Kakheti as a frequent target. Kakhetian villages were regularly attacked by small groups of Lezghins, Northern Caucasions of Muslim faith, from Dagestan. The Lezghins destroyed property and kidnapped both common people and members of the nobility to use as bargaining chips in prisoner exchanges with the Russians.

Shamil’s hostage-taking was partly driven by the hope that the Russians would exchange his son, Djemal-Eddin, for these captives. In 1839, when Djemal-Eddin was six, Shamil sacrificed him as a hostage in a brutal battle with Russian General Alexander Grabbe, to save his followers and the rest of his family. Djemal-Eddin was subsequently reared in Russia by a Georgian aristocrat. After years among the elites of St. Petersburg, he embraced the life of a well-educated European, converted to Christianity, and became an officer in a Russian regiment deployed in Warsaw, Poland. In March 1855, Shamil finally achieved his aim when Djemal-Eddin was exchanged for members of the Georgian Chavchavadze family, who had been taken captive by Shamil’s fighters nine months before.

Gunib, Dagestán circa 1910

In 1859, weary and facing overwhelming odds, Shamil surrendered to the Russians after receiving promises of respectful treatment for himself and his family. He was initially held in the fortified village of Gunib, Dagestán. Soon after, he was sent to St. Petersburg to meet Tsar Alexander II, after which he was exiled to Koluga, a small town near Moscow. He was later allowed to relocate to the more agreeable climate of Kiev, where the Russian imperial authorities provided him with luxurious accommodations. In 1869, he was granted permission to make the pilgrimage to Mecca. He died in Medina, the city of the Holy Prophet, while visiting the city in 1879. Two of his surviving sons became officers in the Russian army, and two others served in the Turkish army.

Shamil's Surrender in 1859

The Siege of Tsinandali

In July 1854, Shamil ordered 10,000 of his soldiers to enter the Georgian province of Kakheti to capture Georgian nobles loyal to the Russian Empire and to destroy the estate of Tsinandali, frequented by the European nobility. Some of the troops were instructed to return with their captives to Dagestán, while other troops were to forge ties with Seid-Ahmad-Emin-Bey, the Turkish Ambassador in the Georgian capital of Tbilisi.

On the day of the attack, David Chavchavadze, the commander of the Kakheti regiment and owner of Tsinandali, was on urgent business in the nearby Kvareli area, and only women, children, and servants were at home on the estate. Anna Drancy, the French governess of David Chavchavadze’s children, was among the household members taken captive by Shamil’s fighters. She described the assault in her memoirs:

The Tsisnandali peasants recommended that Countess Chavchavadze flee to the woods together with her children, since the village had been put to fire and the danger was imminent. The female family members started packing valuables, but it was late in the day. The women and children had the time to merely hide in the palace belvedere overlooking the garden; the belvedere was [soon] inundated with the fighters wearing turbans. First, there were about fifty of them but their numbers increased immensely. Getting off their horses, they ran into the palace, stepped over one of their fellow fighters lying dead, and entered the palace with fierce exclamations. With no resistance on the part of the Georgians, they were all the more encouraged and ran about the 22 chambers of the palace, hoping to find the valuables. They took everything they came across: jewelry, porcelain, wools, and laces, of which they knew nothing and had never seen before. What they could not take away, they smashed. Everything was taken: sugar, tea, coffee; the semi-savages even tasted make-up in jars, and some swallowed camphor oil, which they assumed was an ingredient of Georgian cuisine. One even tried to make another eat a piece of chalk. The sight was both disgusting and appalling.

Yelling, the triumphant Lezghins were approaching the belvedere, so much so that we could hear their steps and were overwhelmed with sadness. We all knelt down. ... The Lezghins forced the door open and rushed into the small tower on the top of building. The stampede started. The screams of the victims and the fierce yells of the attackers joined in a hum. The citadel of the belvedere proved to be hard to take over, for all the women put up a fierce resistance. But all their efforts were in vain. The Lezghins pulled them out of the belvedere. The staircase succumbed to the weight of the people and collapsed. We all were driven out into the yard, which was in an appalling [condition], filled with cattle, carts upside down, disheveled and weeping women in torn clothes; the results of the violence were seen clearly. After that, a horrible tragedy took place just in front of me. A violent fight for Anna, the prince’s wife, broke out among the Lezghin fighters. It took them some time to find out who she was. She was taken to a fierce looking, black-mustached Lezghin with a gun in his hand. He was distributing captives and giving orders to keep an eye on us and to shoot on the spot if anyone tried to escape.

Shamil's seraglio where he kept the hostages

(click for a larger image)

Afterwards, Anna Drancy recounts the hard trip to mountainous Dagestan, abuse by the Lezghins, and suffering that lasted until they reached Shamil’s fortress on the Gunib plateau. The wife and children of David Chavchavadze and the family’s guests—who found themselves in captivity quite by chance—proved to be the most valuable trophies taken from Tsinandali by the Lezhgins. In exchange for them, Shamil demanded the return of his son Djemal-Eddin, the release of about 100 Caucasian captives, and a ransom of one million rubles.

According to Anna Drancy, the 23 hostages were kept in more-or-less reasonable conditions at Shamil's camp, at Dargo-Vedin. Their captivity lasted for almost nine months, during which the prisoners met Shamil on several occasions, such as when he asked Anna Chavchavadze to write a letter to her husband concerning the ransom. In detailed accounts of Shamil's life at the aul, Anna Drancy mentioned Shamil's Austere, disciplined behavior.

However, David Chavchavadze, all of whose property had been destroyed or stolen in the raid, could not afford the ransom. Nor was he initially able to secure the exchange of Djemal-Eddin from the Russian authorities. Shamil would not back down, and David managed to collect 35,000 pieces of silver and 5000 pieces of gold from various sources, including relatives. After several failed attempts, Shamil was finally persuaded to accept these currencies as a ransom payment, and the Russian Tsar, Alexander II, agreed to return Djemal-Eddin to his father. David was instructed to exchange Shamil’s son for the Georgian hostages in the village of Khasav-Jurt, Dagestan. On March 10, 1855, the exchange took place on the banks of the river Michik.

Epilogue

Djemal-Eddin’s return to his home country had a tragic epilogue that proved to be an ominous foreshadowing of misfortunes shortly to befall Shamil and his cause. Having become accustomed to a more civilized urban environment, Djemal-Eddin found life in the Caucasian mountains unbearable, and he chafed under the restrictions imposed upon him. He soon fell ill and died. Not long afterwards, Russian troops led by General Alexander Baryatinsky were readying for an assault on Shamil’s fortress in Vedeno, and a reward for Shamil’s capture was posted. In the summer of 1859, a bloody series of battles broke out in the Caucasian mountains, exacting a huge toll on both sides. However, due to their advanced military tactics, the Russians were eventually victorious, and their promises of an honorable exile for Shamil and his family—and peace for Dagestan—convinced the Imam to surrender.

Source bibliography:

- Baddeley, John Frederick. Russian Conquest of the Caucasus. New York: Russell and Russel, 1965.

- Gammer, M. Muslim Resistance to the Tsar: Shamil and the Conquest of Chechnia and Daghestan. London, 1994.

- Griffin, Nicholas. Caucasus: A Journey to the Land Between Christianity and Islam. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- Haxthausen, August, Freiherr von. Tribes of the Caucasus. With an Account of Schamyl and the Murids. London: Chapman and Hall, 1855.

- Mackie, J. Milton. Life of Schamyl; and Narrative of the Circassian War of Independence Against Russia. Boston: J. P. Jewett and co., 1856.

- Maryam, Jameelah. Two Great Mujahidin of the Recent Past and Their Struggle for Freedom Against Foreign Rule.Lahore, Pakistan: Mohammed Yusuf Khan, 1990.

- Morell, John Reynell. Russia and England: their Strength and Weakness. New York, Riker: Thorne and co., 1854.

- Moser, Louis. Caucasus and its People, With a Brief History of their Wars, and a Sketch of the Achievements of the Renowned Chief Schamyl. London: D. Nott, 1856.

- Verderevskii, Evgenii Aleksandrovich. Captivity of two Russian Princesses in the Caucasus; including a Seven Months’ Residence in Mhamil’s Seraglio. London: Smith Elder and co., 1857.

- Wagner, Friedrich, Dr. Schamyl and Circassia. London: G. Routledge and co., 1854